Lots of consumers say that they’re trying.1 Polling data from the UK suggests that nearly half (44%) of consumers try to buy less meat “All the time” or “Fairly often”.2

They could switch to plant protein food such as beans, peas, and lentils. But people eat meat for other reasons: for the taste; the texture; and their familiarity with particular meals.

Meat substitutes let people reduce the impact of their diet without radical changes to the meals that they eat. Swap a beefburger for an Impossible Burger®. Or chicken for Quorn© chicken pieces.

But are they really better for the climate? They’re usually processed, need energy from manufacturing, and include ingredients that have been shipped from overseas.

This is a basic but crucial question. I thought it would be easy to find a clear answer. But I struggled to find many comparisons based on solid data. There was certainly no centralised dataset that brought them together.

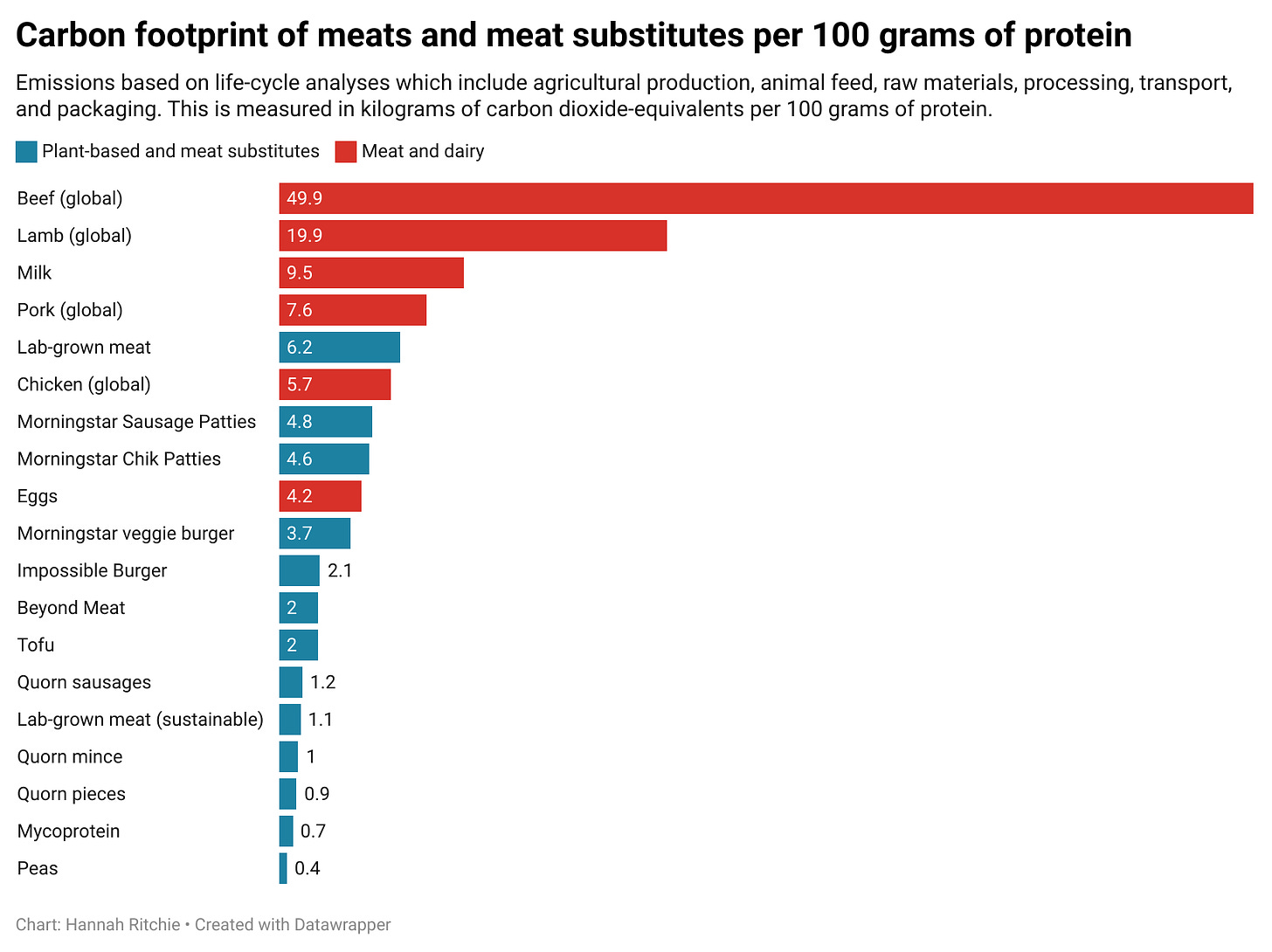

So I tried to build one. You can access it here. I’ve graphed the main results below. The sources and methodologies for each are given at the end of the post.

This is a live and imperfect dataset that I’ve built from publicly available analyses: if you know of other meat substitute products that should be included, then let me know.3

The main takeaway from the data is that most meat substitutes have a lower carbon footprint than meat, and much lower than beef or lamb.

Most meat substitutes are better for the climate than meat and dairy

To compare the carbon footprint of different foods fairly we need to look at their impact across the entire supply chain.4

To do this, we compare them using life-cycle analyses (LCAs): these include not only the impacts on the farm, but also raw materials used for their production, processing, packaging, transport, and distribution.

For meat substitutes, I’ve built a database using publicly available LCAs. I’ve included full details of these analyses at the end of this post.

I’ve tried to make sure that the analyses are comparable: the stages of the life cycle that are included need to be the same, and match the life cycles used for meat and dairy products.

In the chart, I’ve shown the greenhouse gas emissions of a range of meat substitutes compared to meats, dairy, and plant products.5

Let’s compare on the basis of protein since people are often looking for high-protein alternatives to meat.

All meat substitutes have a lower carbon footprint than beef or lamb. Emissions from Quorn© products are 35 to 50 times lower than beef. Switch your beefburger for a Beyond Meat© or Impossible Burger® and you’ll cut these emissions by around 96%.

Replacing beef or lamb can make a big difference. The impact of replacing chicken – the lowest-carbon meat – is much smaller.

Lab-grown (cultivated) meat is actually worse than chicken. At the moment, at least. This is because lab-grown meat needs lots of energy.

But, unlike chicken, lab-grown meat is still young. It’s an emerging technology. We can bring its footprint down through improvements in energy efficiency, but also by decarbonising our electricity supply. We need to do this anyway if we’re going to tackle climate change. If we power lab-grown meat with renewable or nuclear electricity, it could have a much smaller carbon footprint.

We see this from the chart – for the ‘sustainable’ lab-grown meat – where the electricity is powered from solar, wind, and nuclear. In this case, it becomes one of the lowest-carbon foods.

Meat substitutes are also lower-carbon than meat from the US or Europe

Above, we compared meat substitutes to the global average footprint for meat products.

But this probably overstates the benefits for consumers in the US, Europe, and other countries with productive farms. Beef produced in the US or Europe tends to be lower carbon than beef produced in Brazil.6

So, let’s see if meat substitutes still have a lower footprint than meat produced in rich countries. To stress-test this, for Europe, I’ve included meat products with some of the lowest emissions.

Meat Processing – From Farm to Table

Meat Processing – From Farm to Table

The carbon footprint of meat substitutes is around ten times lower than beef from the US or Europe. They’re also lower than pork from either region, and chicken produced in the US. Chicken from Europe has a similar footprint as the Beyond Meat© or Impossible Burger®.

In their large global meta-analysis, Joseph Poore and Thomas Nemecek found that some of the lowest carbon beef in the world emitted around 10 kilograms of CO₂eq per 100 grams of protein. That’s still five times higher than the Beyond Meat© or Impossible Burger®, and ten times higher than Quorn©.

Meat substitutes tend to be better for the climate, regardless of where your beef, pork, or chicken is produced.

Companies need to do a better job of backing up their environmental claims with data

I wasn’t surprised by the results of these comparisons. I know, simply by looking at the ingredient list of meat substitutes, that they should have pretty low carbon footprints.

What I found surprising was how few companies published their environmental footprints publicly. Nearly every meat substitute brand makes claims about how much better their products are for the environment. These claims are largely true.8 But it’s painful to see them made without transparent, public analyses to back them up.

The dataset I built is imperfect and incomplete. I did the best I could with what data and reports I could find.

It shouldn’t be this way. Every claim that a brand makes should be backed up with transparent, publicly available data. Ideally, these analyses would be done by academics or a single, independent evaluator.

One downside to the rare reports that we do have is that they’re self-funded. The companies hire independent consultancies that specialise in environmental footprinting.9 There’s no reason to believe that this would bias the results. But the optics of self-funded reports don’t look great.10 It makes them easy to discredit.

Meat substitutes also use less land, making their climate benefits even greater

One final note. Most meat substitutes have lower greenhouse gas emissions than meat and dairy. But their climate benefits are even greater when we account for the fact that they use much less farmland.

To produce 100 grams of protein from beef in the US needs around 27 times as much land as the Beyond Meat© burger. Chicken and pork need around six times as much cropland for animal feed.

This land use comes at a cost: a ‘carbon opportunity cost’. If we weren’t using it for farmland we could leave it to regrow natural vegetation such as forest or wild grasslands. This would sequester carbon from the atmosphere.

To get the ‘total’ carbon footprint of foods we can combine emissions from their production and supply chain – that we looked at above – and these opportunity costs.

In a future post I’ll try to calculate what these opportunity costs are, so we can compare the total carbon footprint of meat substitutes.