In late May 2022, global headlines in publications such as The Economist, The Washington Post and the Financial Times focused on the rising crisis of global food insecurity.

The Economist magazine featured a cover story entitled “The coming food catastrophe”. This is a reality that the developing nations finds themselves in since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war. The effects of the war on grains and oilseeds markets[1], along with the ban on exports of wheat by India and a temporary ban on palm oil exports by Indonesia[2], respectively, has added to the anxiety in the markets and negatively affected the food-import dependent countries. This is in an environment where agricultural commodity prices were already elevated as a result of a relatively poor harvests in South America, and parts of Asia, along with rising demand for grains and oilseeds in China.

There are rising concerns about the 2022/23 global grains and oilseeds supply amid dryness in parts of the US, and Europe, where planting remains behind the usual pace.[3] In addition, there are fears that higher fertiliser prices could prompt some farmers to reduce their usage. All of this will have consequences for yields at the end of the 2022/23 season, and subsequently food security. The developed nations tend to have some level of buffers during such times, through income support and support to farmers, amongst other instruments. But the developing countries tend to be more adversely affected, particularly those with poor agricultural production, and limited fiscal space to support farmers and households. The African countries, and perhaps South Africa, to a lesser extent, are in this more vulnerable category. This note reflects, very briefly, on Africa’s current food security matters and elaborates on the situation in South Africa specifically.

Africa’s food conditions

The African continent is a net importer of food and agricultural products worth roughly US$80 billion a year, according to data from Trade Map.[4] In the East Africa region, the conflict in regions of Ethiopia, for instance, had already displaced farmers and resulted in concerns about food insecurity.[5] The drought in the region, leading to potentially poor harvests in Kenya, among other countries, was a pre-existing challenge that will now be exacerbated by the Russia-Ukraine war’s disruption on grains and oilseeds, along with fertiliser and fuel prices.[6] These factors have compounded the concerns about food insecurity in the African continent.

Do we face food insecurity in South Africa?

Here in South Africa, the picture is slightly different from most African countries, at least from the food availability perspective. We don't foresee a shortage of food supplies. The major impact of the disruptions in global agricultural markets will mainly be through price transmissions. South Africa is generally a net exporter of food and agricultural products and has had sizable harvests in the past few years, with an expected good crop in the 2021/22 season. The primary food staples the country imports are wheat, rice, palm oil, and poultry products. From discussions with major importers of these products, we believe that the country has secured sufficient supplies to last for some time.

In the case of domestic food prices, which are a major risk, the picture remains mixed. For example, the April 2022 data released by Statistics South Africa showed that the country's consumer food-price inflation decelerated to 6,3% y/y in April 2022 from 6,6% y/y in the previous month. This is on the back of relatively softer price increases in meat, milk, eggs and cheese, and vegetables.

These data are roughly within our expectations, and the food products’ price variation will likely persist in the coming months. In other words, fruit, vegetables, milk, eggs and cheese, and to a lesser extent, meat, could see softer price increases in the coming months. Meanwhile, grain-related products and oils and fats could register notable price increases. This will mirror price movements in the global agricultural markets.

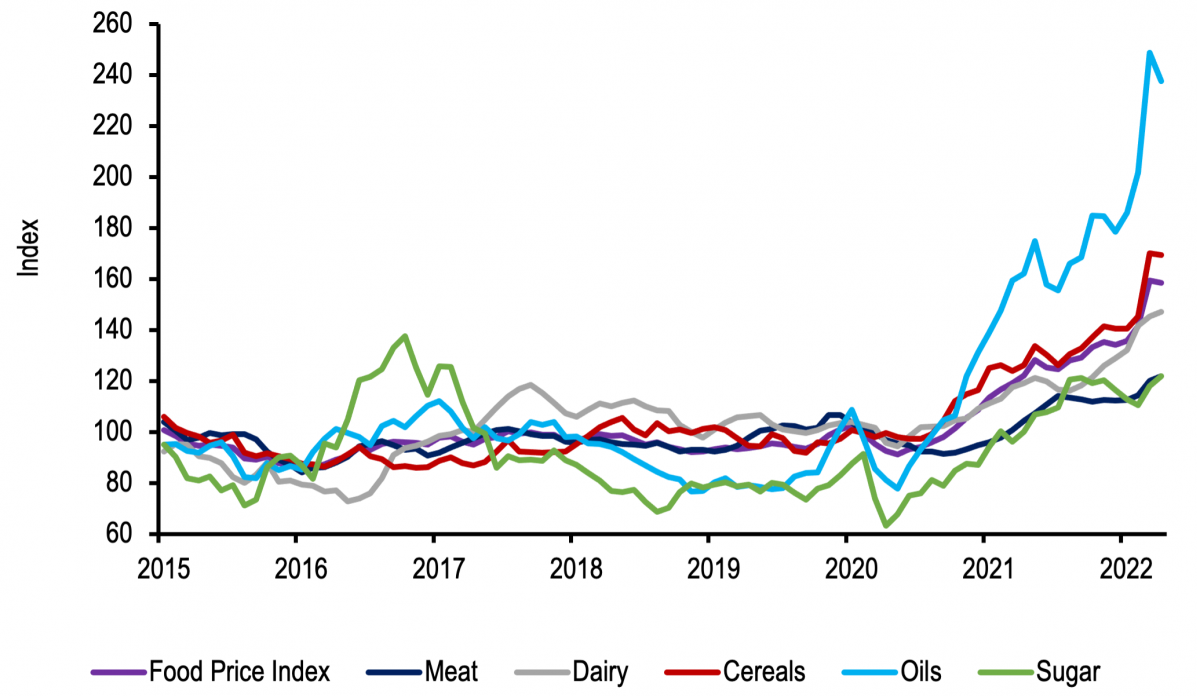

For example, since the war in Ukraine began and disrupted the global grains market, the agricultural commodity prices have increased significantly, with the FAO's Global Food Price Index in April averaging 158 points, which is up 30% y/y, coming from a record high in March. But the temporary ban on palm oil exports, which Indonesia’s government imposed between the end of April and mid-May 2022 (which has now been reversed), and a similar ban on wheat exports by India, and the expected lower wheat harvest in the 2022/23 production season had since added renewed upside pressures to agricultural commodity prices. These will likely reflect on the FAO's Global Food Price Index update to be released in June 2022.

Figure 1: FAO Global Food Price Index

Source: FAO, data as at 06 May 2022

As South Africa is intrinsically linked to the global agricultural markets, it has also experienced increased agricultural commodity prices. Thus there is a potential uptick in prices of cereals, and oil and fat products in the consumer food-price inflation basket. The additional upside risk to the domestic market is also the rise in fuel prices.

In the case of fruits and vegetables, South Africa has a sizable harvest, and the disruption in fruit exports within the Black Sea region could also add downward pressure on domestic prices due to increased supplies that would have ordinarily gone to exports. One product whose price trend remains uncertain is meat. The recent outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease have led to the temporary closure of some key export markets for the red meat industry, thus adding downward pressure on prices. Conversely, there are fears of a potential increase in poultry product prices, which could lessen the benefit of softer red meat prices.[7]

Conclusion

Overall, various factors in the food market push in opposing directions in the short term. That said, we believe South Africa's consumer food price inflation could average just over 6% y/y in 2022 (from 6,5% in 2021). The base effects, along with meat, fruits, and vegetables, will likely keep food price inflation somewhat contained in the months ahead.

In essence, South Africa has its fair share of challenges regarding food security, but the conditions here are not as dire as expected in some regions of the world. The story of "The coming food catastrophe", as The Economist magazine puts it in the 21 May issue[8], might be a reality for many parts of the world, but South Africa seem to be well cushioned against it, at least at a national level in the near term. There are, of course, severe cases of food insecurity at household level in South Africa, which are the results not only of higher food prices but the general absence of household income.[9] This is a question of socio-economic policy, not merely agriculture and the food industry.

[1] Sihlobo, W. 2022. How Russia-Ukraine conflict could influence Africa’s food supplies. Johannesburg: The Conversation.

[2] The ban has now been lifted; more information is here.

[3] More information about crop planting progress in the US is available here.

[4] Trade Map (2022). Available here.

[5] More information about how the conflict affects food security is available here.

[6] Sihlobo, W. 2022. Changes in sub-Saharan maize trade spell potential trouble for Kenya. Johannesburg: The Conversation.

[7] More information is available here.

[8] The Economist cover story is available here.

[9] Some information on food insecurity in South Africa is available here.