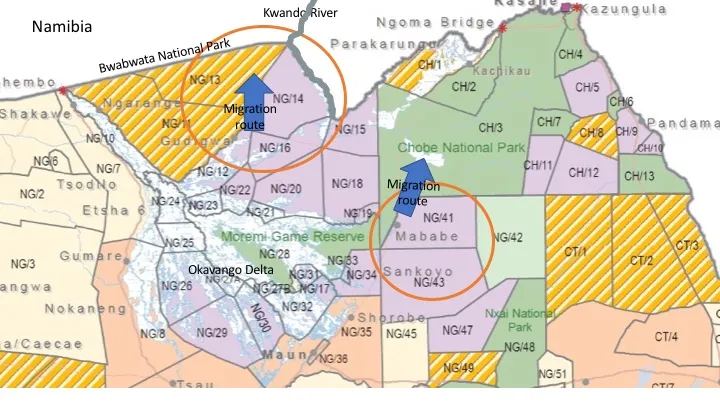

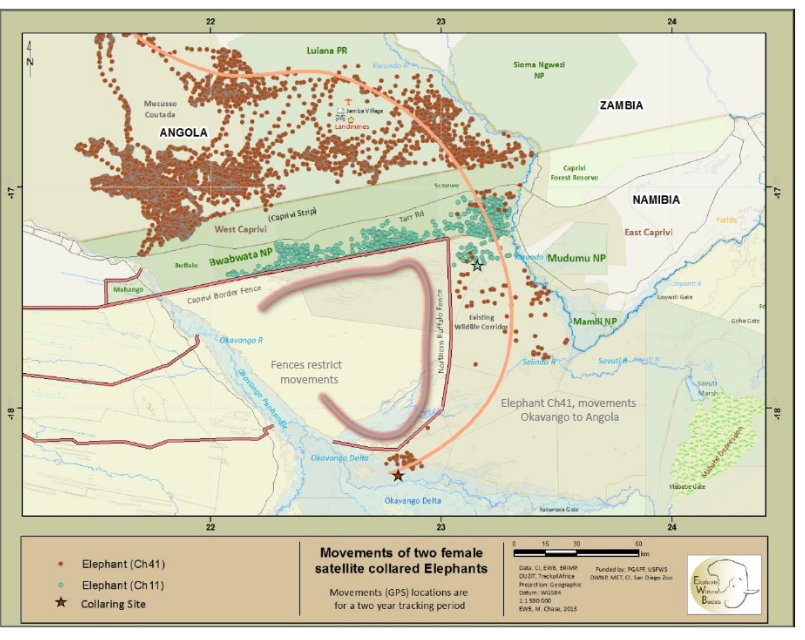

One of their main dispersal routes as they move from the Okavango Delta and central Botswana is northwards along the Kwando River into Namibia, Angola and Zambia and from the Okavango Delta to the Chobe River. These areas provide some of the finest wildlife tourist viewing in the world.

One of those corridors, NG13 (NG stands for Ngamiland), was recently declared open for trophy hunting. Last month, one of the region’s largest-tusked elephants was shot there by an American client of the professional hunter Leon Kachelhoffer, acting on behalf of Derek Brink (of Derek Brink Holdings), one of Botswana’s richest men. The huge animal had tusks weighing 48kg (105.8 lbs). The hunt has caused outrage among conservationists around the world.

His lodge Qorokwe in NG32 is listed seamlessly as a Wilderness Safaris-branded camp and is booked through the company. The Wilderness website describes it as having a well-deserved reputation as a top Botswana safari destination, but does not reveal any link to its professional hunter owner.

When it was opened, Wilderness Safaris Botswana managing director Kim Nixon said: “We are thrilled to be partnering with the Calitz family to reveal this exclusive new land-based camp and private concession — a highly-productive game-viewing area that has been unutilised for the past four years.”

Another hunt planned

In a podcast, responding to criticism of the NG13 hunt, Kachelhoffer’s disingenuous reply to Blood Origins host Robbie Kroger was “when you take a bull like that, there’s a lot of remorse, there’s a lot of sadness, you think about the great life that this elephant has led.”

According to the Tcheku Community Trust, he will be returning to NG13 with a client on May 28 to shoot another super-tusker.

The Masisi government has given many reasons for the resumption of hunting after the previous president, Ian Khama, banned it in 2014. It claims there are too many elephants, that this is causing human-animal conflict and that hunting supports the local population.

There are counter-arguments. Aerial surveys have shown that Botswana’s elephant population has been stable for many years, NG13 is sparsely populated and there has been no conflict with elephants. In an area empty of people other than a few cattle posts, this is clearly not an argument that can hold water. Neither does the claim that old bulls are redundant.

According to Dr Audrey Delsink, wildlife director of Humane Society-Africa, Botswana’s management choices like hunting in migration corridors could have devastating consequences for transient elephants.

“Trophy hunters predominantly hunt the biggest, oldest elephants. Targeting these elephants is extremely detrimental to the population because they provide critically important ecological and social knowledge and aid the survival of the entire group. Older bulls control musth in younger, inexperienced bulls who otherwise manifest delinquent behaviour.

“A 2014 study in the Mapungubwe Transfrontier Conservation Area found that at the current rates of hunting, under average ecological conditions, trophy bulls would disappear from the population in less than 10 years, with ripple effects that will far outreach the target zone and population, for many generations.”

Mali’s elephants show how people and nature can share space in a complex world

Mali’s elephants show how people and nature can share space in a complex world

Another issue is the degree to which communities benefit. Kachelhoffer paid the Tcheku Community Trust P200,000 for each elephant — that’s around $16,500. For an elephant that size, the cost to the client could be between $80,000 and $100,000.

The value of an elephant is not just about who gets paid and how much. Trophy hunting is selling elephants far short of their worth and essentially constitutes theft to the tourist industry and to carbon sequestration. A study by the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust calculated that, at the time of the study, an elephant might be worth $30,000 as a trophy and, if poached, its ivory on the black market would fetch $21,000. As a living elephant, its worth to tourism over its lifetime would be more than $1.6-million. That means that an elephant is worth 53 times more alive than as a trophy.

By nature of their browsing and composting, elephants, also sequester carbon by thinning trees and spreading seeds to generate new growth. In this way, they maintain optimal carbon capacity and oxygen generation in the landscape. Valued in carbon credits at a minimum of $15 a tonne, the study estimates 415,000 savanna elephants are worth $86.6-billion, or more than $200,000 each. Add forest elephants and that jumps to $129.6-billion.

When looked at this way, says environmental economist Ross Harvey, justifying an elephant trophy hunt at, say, $46,000 would appear economically absurd. But for trophy hunt outfitters, it’s money in the bank.

Hunting may now be legal in Botswana, but is the hunting of Africa’s last remaining tuskers in one of the most important wildlife corridors in Africa ethical? Hunters like Johan Calitz and Leon Kachelhoffer would, in all likelihood, argue that legal means ethical.

Derek Brink, one of Botswana’s richest men, has a 50% shareholding in Spar supermarkets in Botswana and owns Senn Foods, Botswana’s largest producer of processed meat. He’s the largest landowner with farms in the Tuli Block and is Kachelhoffer’s boss. Together they recently bought hunting rights to NG13 from the local community.

The chairperson of NG13’s Tcheku Community Trust, Peter Kerapetse Bantu, said the community had a quota for four elephants and they sold this and rights to the area to Brink and Kachelhoffer.

“NG13 hasn’t been hunted all along,” he said, “so this area has been the hiding place for these big elephants. There’s never been ploughing of fields, only a few cattle posts along the buffalo fence. But there are waterholes and these elephants can live there undisturbed. So we are not shocked that such big elephants are found there.”

He said the hunt took place near the boundary of NG14 which includes the Kwando River corridor. There are now three elephants left on the quota. Keckelhoffer phoned to tell Bantu he would be coming with a client on 28 May 2022. “American client I think.”

Undermining the Kaza corridors

The problem with permitting hunting in the Kwando corridor, which includes NG13, is that it undermines a five-country initiative to wildlife access routes and will create landscapes of fear, blocking migration routes in the 30km bottleneck into the Bwabwata National Park in Namibia.

Similarly, hunting in NG41 puts guns on the critical migration route between the Okavango Delta through Chobe National Park and into Zimbabwe.

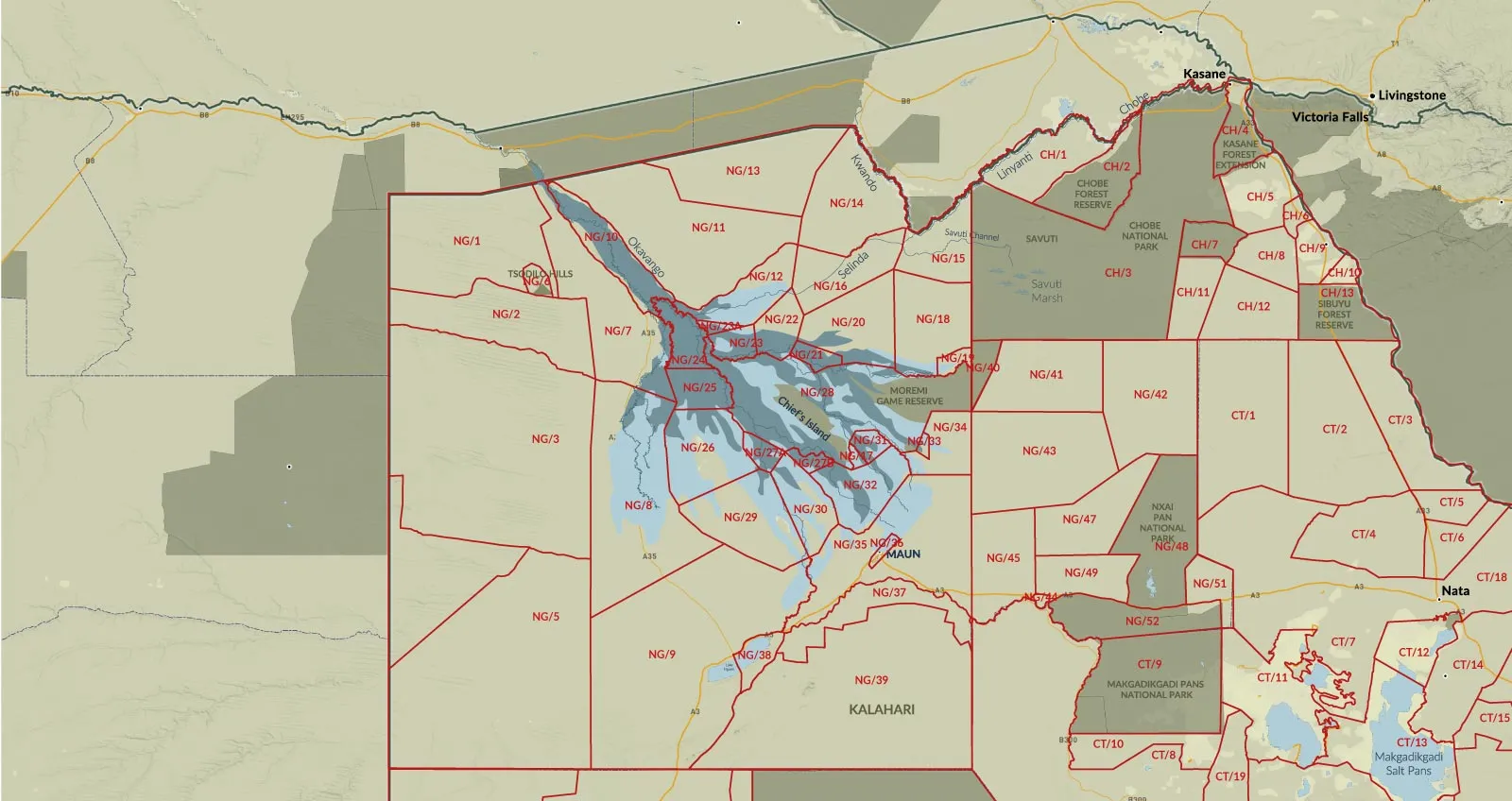

The areas where both hunts took place is part of the visionary Kavango Zambezi (Kaza) Transfrontier Conservation Area, a vast area spanning five countries established to protect migration corridors.

The initiative seeks to create one of Africa’s most important wildlife refuges. It’s the world’s largest transfrontier conservation area, spanning around 520,000km2 (almost the size of France) and covers the Okavango and Zambezi river basins where the borders of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe meet.

It includes 36 national parks, game reserves, community conservancies and game management areas, most notably Chobe National Park, the Okavango Delta (a Ramsar Site) and the Victoria Falls (a World Heritage Site).

Tourists and hunting

Then there’s the question of the optics of hunting and tourism. Johan Calitz Safaris claims to be the largest elephant hunting outfitter in Africa, with 95 elephants on quota every year. For five years in a row, it has boasted the highest ivory average of all outfitters in the country.

Yet Qorokwe Lodge, belonging to Calitz, is being marketed by Wilderness Safaris. This is a company that prides itself on ethical tourism sold to high-income clients and is majority-owned by The Rise Fund whose membership reads like a Who’s Who of billionaire philanthropists.

They include the singer Bono, Richard Branson, Laurene Powell Jobs (wife of Steve Jobs of Apple), the founder of eBay Jeff Skoll, Mellody Hobson (wife of Starwars creator George Lucas) and chairperson of Starbucks, Linkedin chairperson Reid Hoffman, Anand Mahindra who chairs the Mahindra motor corporation and Paul Polman, former president of Procter & Gamble and presently US CFO of Nestlé.

Do they know their company is marketing a lodge belonging to one of Africa’s biggest trophy hunters? Probably not. But when tourists make bookings through Wilderness Safaris, they should keep this in mind.

Meanwhile, Calitz and Kachelhoffer will be cleaning their rifles awaiting the arrival of foreign clients eager to hang huge, brag-worthy trophies on their walls.