Hollard Insure and Farmingportal.co.za and Agri News Net - Young Agri Writers awards

Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD) has become a familiar headline in South Africa, to the point where many now regard it as a problem that refuses to go away.

Each outbreak triggers renewed concern in the media and among industry stakeholders, yet the disease persists despite years of debate and official interventions. To move beyond the cycle of alarm and short-term fixes, it is necessary to ask why FMD continues to resurface, what role vaccines play in its control, how the disease affects the red meat industry, and what lessons can be drawn from countries that have managed it more effectively.

1. Why FMD Remains a Persistent Challenge

FMD is among the most contagious livestock diseases worldwide, threatening cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs. Caused by an Aphthovirus in the Picornaviridae family, it spreads rapidly through aerosols, direct animal contact, and contaminated equipment or vehicles (WOAH, 2023). The speed of transmission makes outbreaks particularly hard to contain, especially in high-density farming regions. The consequences are severe: infected animals suffer reduced milk yields, slower weight gain, fertility problems, and high calf mortality. At the same time, trade partners immediately suspend imports of live animals and red meat products once FMD is detected. South Africa has repeatedly faced such suspensions, with high-value markets in the EU, China, and the Middle East closing overnight (BFAP, 2023). The financial losses from disrupted exports often exceed the direct farm-level costs of the disease, highlighting its systemic economic impact.

A key reason the virus remains so difficult to control lies in its genetic diversity. There are seven serotypes worldwide - O, A, C, Asia 1, and the Southern African Territories (SAT) 1-3 - and within each serotype are multiple topotypes and strains that evolve rapidly. Immunity to one offers little or no protection against others (Maree et al., 2020). In Southern Africa, the SAT strains dominate and are maintained in African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), which act as long-term carriers. At the buffalo-cattle interface, especially near the Kruger National Park, the virus regularly spills over into domestic herds (Vosloo et al., 2002). A simple analogy helps: each strain can be thought of as a different type of lock, and a vaccine as a key. A key cut for one lock cannot open another. The SAT strains in Southern Africa are like locks that are constantly being reshaped, so even when a key fits one season, the next year’s virus may have already changed, leaving livestock unprotected.

*I HAVE EMAILED THE DIAGRAM THAT SHOULD BE INSERTED HERE

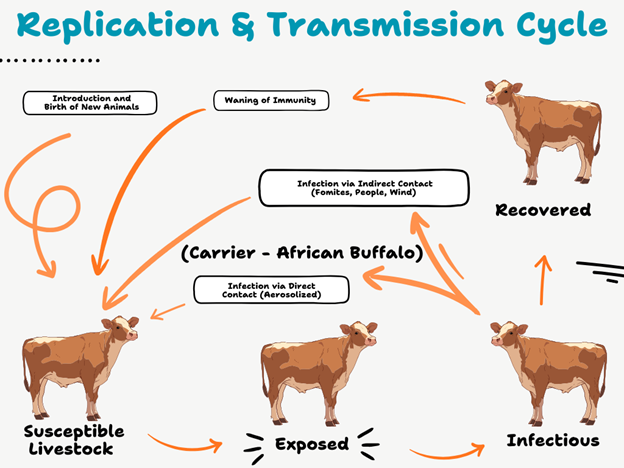

Figure 1: Transmission cycle of Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD)

This schematic illustrates the SEIR (Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Recovered) dynamics of FMD in livestock. New animals enter the susceptible group (S), which can become exposed (E) through direct contact with infectious animals (I) or indirect transmission via fomites. Exposed animals then progress to the infectious stage, shedding virus into the environment and perpetuating the cycle. Outcomes include recovery (R) with temporary immunity, progression into a carrier state (C) where ruminants harbour the virus without clinical signs, or death/slaughter. Immunity wanes over time, returning recovered animals to the susceptible pool. Wildlife reservoirs, particularly African buffalo, play a critical role in maintaining virus circulation and reintroducing infection into domestic herds. The diagram highlights the multiple routes of infection and the challenges of controlling FMD in endemic regions.

Source: (Adapted from Paton, Gubbins and King, 2018)

In this context, eradication is not realistic. While many developed countries eliminated FMD by culling infected herds and imposing strict movement controls, that strategy is not feasible for South Africa. Wildlife reservoirs ensure constant re-emergence, and the economic and ethical costs of mass culling would be severe (Thomson et al., 2003). Vaccination remains the only sustainable option: it reduces clinical cases, slows transmission, and helps maintain zones with conditional export approval (Paton et al., 2009).

For vaccines to be effective, however, three conditions must be met. They must be closely matched to circulating strains, coverage has to be wide enough to build herd immunity, and distribution must be reliable with cold chains preserved to maintain potency. Breakdowns in any of these three elements leave herds exposed. South Africa has long recognised this reality, which is why vaccination campaigns are routinely conducted in high-risk provinces such as Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and KwaZulu-Natal. Yet these efforts remain uneven. Supply has often been disrupted by production failures at Onderstepoort Biological Products (OBP), South Africa’s only licensed manufacturer. When OBP falters, vaccines must be sourced from the Botswana Vaccine Institute (BVI) or Zambia, but regional demand means South Africa often faces delays and higher costs (DALRRD, 2022).

The consequences of unstable supply ripple across the economy. Herd immunity is undermined, outbreaks spread more widely, and export bans last longer. Each suspension erodes South Africa’s reputation as a reliable supplier, making buyers cautious even after trade is restored. Stable vaccination is therefore more than a veterinary tool: it is a cornerstone of trade competitiveness and rural livelihoods.

2. Why South Africa Still Depends on Imports

Despite having both research capacity and a state-owned manufacturer, South Africa remains heavily reliant on imported FMD vaccines. This dependence reflects the complexity of local viral strains, weaknesses in domestic production, limited economies of scale, and slow regulatory processes. Together, these factors leave the system unable to provide consistent protection without external support.

One of the most fundamental challenges is the virology itself. Whereas most regions of the world deal with one or two dominant serotypes, Southern Africa faces three highly diverse SAT strains that evolve quickly. Immunity to one topotype rarely protects against another, meaning vaccines must be closely matched to circulating field strains (Maree et al., 2020). Global producers tend to concentrate on Eurasian and Latin American serotypes, leaving Southern Africa dependent on specialised regional suppliers such as Botswana’s BVI.

Domestic production capacity has long been constrained by the condition of OBP, South Africa’s sole licensed producer. Established in 1908, OBP has struggled in recent decades to maintain consistent output. Ageing infrastructure, equipment failures, and lapses in biosafety certification have led to repeated stoppages and inconsistent supply (WCG, 2019). Quality-control problems have eroded producer confidence, while governance and funding difficulties have delayed essential upgrades.

Scientific expertise exists, but institutional roles are fragmented.

The Agricultural Research Council’s Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute (ARC-OVI) provides critical surveillance and diagnostics, maintaining reference strains and tracking outbreaks. Yet ARC has neither the mandate nor the facilities for vaccine manufacturing. In practice, ARC generates the knowledge needed to update vaccines, but OBP is the only body authorised to produce them - and too often it cannot meet the demand. This gap between research and production explains why South Africa frequently falls back on imports when outbreaks occur.

Scale adds another layer of difficulty. Vaccine production is capital-intensive, requiring high-containment laboratories, specialist inactivation processes, and highly skilled staff (Doel, 2003). In countries with large cattle herds, such as Brazil and India, high domestic demand allows costs to be spread across vast numbers of doses, making production commercially viable (OECD/FAO, 2022). South Africa’s smaller herd size prevents similar economies of scale, whereas regional producers like BVI and Zambia serve multiple markets, enabling them to sustain higher output at lower cost per dose.

Even when vaccines are successfully manufactured domestically, distribution is slowed by regulatory and procurement hurdles. The approval of new strains requires lengthy testing and authorisation, while national tender processes delay procurement at precisely the moment rapid deployment is most critical (DALRRD, 2022). Botswana offers a useful contrast: by integrating laboratory surveillance and vaccine production within BVI, the country ensures a far quicker turnaround when new strains emerge.

The outbreaks of 2019-2022 exposed the fragility of this arrangement. Regional demand surged, stretching supplies from BVI and Zambia, and South Africa was forced to compete with its neighbours for limited doses. Prices rose, deliveries were delayed, and export suspensions dragged on, costing the red meat value chain billions in lost sales (RPO, 2022).

South Africa’s dependence on imports is therefore not merely a temporary fallback during production shortfalls. It reflects the underlying fragility of a system shaped by complex local strains, a monopoly producer constrained by ageing facilities, a structural gap between research and manufacturing, and regulation that moves too slowly. Imports can provide short-term relief, but without institutional reform the country will remain exposed to shortages and vulnerable to regional competition in times of crisis.

3. The Cost of Unstable Vaccine Supply

Unreliable access to FMD vaccines carries economic consequences that extend far beyond the farm. Outbreaks directly suppress productivity in affected herds, but the wider costs are seen in disrupted trade, diverted investment, and declining competitiveness. Because FMD is a notifiable disease under the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), instability in vaccination heightens the risk of outbreaks and prolongs export suspensions (WOAH, 2023).

For livestock producers, unstable vaccine supply translates into unpredictable income. Under-protected herds face reduced milk yields, stunted growth, fertility problems, and higher calf mortality (Knight-Jones and Rushton, 2013). Containment measures compound these losses. When cattle cannot be moved to feedlots or abattoirs, farmers are forced to hold stock for longer periods, driving up feed costs, increasing overcrowding, and prompting distressed sales at discounted prices (RPO, 2022). Commercial beef farmers are especially exposed: their greatest losses come when high-value export markets close. Beef that would have fetched premium prices abroad must be redirected into the local market at lower margins, just as outbreak control pushes costs higher.

For consumers, outbreaks create paradoxical price movements. Farm-gate prices may collapse when exports are suspended, but retail beef prices often remain high. Rising feed costs, reduced slaughter weights, expensive vaccines, and escalating transport and logistics charges all keep the cost base elevated (RMIS, 2025). Movement restrictions reduce the supply of slaughter-ready animals, forcing farmers to retain stock for longer, while the deteriorating beef-to-maize price ratio undermines feedlot profitability and discourages downward adjustments in retail prices (Food for Mzansi, 2025). The result is a paradox in which producers lose income while consumers see little relief in store prices.

The heaviest losses, however, are borne by exporters. Market access depends directly on FMD status, and outbreaks trigger immediate bans. During the 2019 outbreak, the USDA reported that suspended markets had purchased US$90 million of South African red-meat and live-cattle exports in 2018 (USDA-FAS, 2019). Researchers at the University of Pretoria estimated that the suspension cost the value chain up to R10 billion, with around 3 000 tonnes of beef exports lost every month (UP, 2019). The damage does not end when restrictions are lifted: buyers often impose stricter sanitary conditions, reduce volumes, or shift to suppliers with more reliable health regimes. These reputational effects can linger for years, compounding the immediate financial blow.

Perhaps the most damaging consequence of instability is its deterrent effect on investment. The Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy (BFAP, 2023) and the National Agricultural Marketing Council (NAMC, 2024) project that, under stable vaccination, beef exports could expand from around 5% to nearly 24% of production by 2030, adding an estimated R12 billion annually to agricultural GDP. Persistent instability locks this growth potential out of reach. Lost exports also mean lost value per kilogram. In 2023, South Africa exported boneless fresh/chilled beef at an average of US$5.83/kg, compared with US$10.85/kg for Australia and US$10.75/kg for the United States (RMIS, 2023). The gap represents the premium foregone whenever FMD suspensions close off high-value markets.

These pressures ripple through the wider economy. The red meat industry contributes substantially to agricultural gross value added (GVA) and supports extensive value chains from feed to retail. Losses on the scale seen in 2019 disrupt rural employment and incomes (BFAP, 2023), while export instability weakens the agricultural trade surplus, with knock-on effects for fiscal revenues and the balance of payments.

Unstable vaccination is therefore not simply a veterinary weakness but a systemic economic risk. It undermines competitiveness, deters investment, and leaves the sector locked out of growth opportunities. Each outbreak compounds these vulnerabilities, pushing the red meat value chain further from its potential.

4. What Other Countries Show Us

South Africa is not unique in facing the challenge of FMD. Other countries with equally complex animal health landscapes have managed to build systems that provide reliable vaccine supply and sustained trade access. Their experience shows that resilience depends less on available resources than on aligning legislation, financing, and institutional design.

Botswana: integrating research and production

In Botswana, success has centred on the Botswana Vaccine Institute (BVI), which functions both as a reference laboratory and as a manufacturer. This integration means that new strains identified in the field can be rapidly translated into updated vaccines (WOAH, 2021). Supported by government funding and regional demand, BVI has grown into a supplier for the Southern African Development Community. Its model demonstrates how combining surveillance and production under one roof creates the speed and responsiveness that South Africa currently lacks.

Brazil: scaling through consistency

Brazil offers a different lesson, showing the value of scale and stability. With one of the world’s largest cattle herds, it has long pursued mass vaccination campaigns coordinated by the federal government. Advance purchase agreements and consistent delivery through private veterinary networks ensure wide coverage and minimise gaps (Pacheco and Brito, 2020). This blend of state leadership and predictable financing has enabled private partners to deliver vaccines efficiently. The result has been sustained access to premium export markets and growing dominance in global beef trade.

Zambia: building capacity with limited means

Closer to home, Zambia shows how capacity can be built even with modest resources. Through steady investment in vaccine facilities and careful alignment with regional demand, it has developed the ability to meet domestic needs while also supplying neighbours during emergencies. Though still smaller than Botswana’s BVI, Zambia’s progress demonstrates that targeted investment, combined with institutional support, can reduce dependence on imports (Muleya et al., 2020).

Türkiye: state-led regional supplier

Türkiye provides another example of how state support can drive resilience. Its Şap Institute, operating under the Ministry of Agriculture, not only supplies the domestic herd but also exports vaccines across the Middle East. This dual role as both a national producer and a regional hub shows how strong state backing, combined with a clear mandate, can build trust in both domestic and international markets (Paton et al., 2009).

India: financing universal access

In India, the key innovation has been financing. By making vaccination free to farmers, the state has ensured wide coverage supported by cold-chain infrastructure and ear-tag tracking systems that verify uptake (Subramaniam et al., 2019). The result has been steady improvement in national herd immunity despite the country’s vast geography and herd size. India’s experience highlights how financial mechanisms, when tied to strong logistics, can overcome resource constraints.

Lessons for South Africa

Across these diverse contexts, the common thread is resilience by design: BVI integrates science and production; Brazil leverages scale and consistency; Zambia advances through steady investment; Türkiye expands through state-led support; and India ensures universal access through financing. What sets South Africa apart is not a lack of scientific expertise or regional importance, but institutions and legislation that prevent similar integration. The lesson is clear: with enabling policy and consistent investment, even resource-constrained countries have built vaccine systems that protect farmers, stabilise trade, and strengthen competitiveness.

5. Fixing South Africa’s Vaccine System

Reforming South Africa’s FMD control system requires addressing its institutional weaknesses rather than applying short-term fixes. Modernisation of OBP is necessary, but it cannot remain the only pillar of vaccine supply. Its facilities must be upgraded to meet international standards, paired with transparent governance, while a structured partnership with ARC would ensure that surveillance and research findings translate more quickly into field-ready vaccines.

Greater participation from private and producer organisations is equally important. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) in areas such as vaccine finishing, logistics, and distribution would reduce the pressure on OBP and introduce new layers of accountability. The RMIS traceability programme illustrates how the private sector is already investing in resilience. Yet traceability cannot resolve systemic weaknesses on its own; it must be matched with reliable vaccine supply and institutional reform.

Financing also needs to move from irregular state allocations to a predictable model. A statutory levy on red meat, administered transparently under NAMC frameworks, could provide ring-fenced funds for vaccine development, surveillance, and emergency stockpiling. Levy systems already support research in other sectors, and with clear audits and reporting, a similar mechanism for red meat could ensure long-term stability.

At the core of the problem lies the Animal Diseases Act (Act 35 of 1984). While designed to protect national biosecurity, Section 20 entrenches a monopoly by excluding private and academic producers and tightly restricting international collaboration (DALRRD, 2022). This rigidity prevents innovation and prolongs shortages. By contrast, countries such as Botswana, Brazil, India and Türkiye have created enabling legal frameworks that allow carefully licensed participation while maintaining state oversight (Paton et al., 2009; Subramaniam et al., 2019; WOAH, 2021). For South Africa, reforming the Act would not mean abandoning biosecurity controls but creating a licensing system that expands capacity, fosters competition, and strengthens accountability.

Without these changes, private initiatives will remain stopgaps and OBP a fragile bottleneck. With them, South Africa could build a system that shifts from reactive crisis management to proactive preparedness, restoring resilience and competitiveness in the red meat value chain.

6. Conclusion and Way Forward

Foot-and-Mouth Disease has exposed the fragility of South Africa’s animal health system. Repeated outbreaks and vaccine shortages have not only disrupted production but also weakened trust, trade, and investment in a sector that should be driving growth.

International experience shows that resilience is possible. Botswana, Brazil, India, Türkiye, and Zambia have built systems that combine legislation, financing, and institutional design to keep vaccination reliable and trade stable. The lesson is that animal health is not a technical afterthought but an economic foundation.

South Africa now faces a clear choice. It can continue managing crises with short-term fixes, or it can pursue reforms that restore resilience and competitiveness. The private sector has already demonstrated its willingness to contribute through initiatives such as RMIS’s traceability programme, but industry efforts cannot substitute for structural change.

If governance is strengthened, financing made predictable, and legislation modernised, the country could move beyond recurring outbreaks to a system that protects farmers and consumers while opening the door to sustained export growth. Reliable vaccination is therefore more than disease control: it is the cornerstone of livelihoods, rural economies, and South Africa’s credibility in global markets.

I am an agricultural economist focused on understanding how natural capital, sustainability goals, infrastructure, and the economic environment shape businesses and strategic development. My expertise spans agribusiness finance, risk analysis, policy evaluation, and macroeconomic modelling, with a strong foundation in data analysis, research project management, and investment advisory.