How much food did the world produce last year? What was the extent of wildfires? How many people died in disasters?

While all of these issues are covered in the media in some form, they’re often reported on as single events: a story about a flood, a hurricane, or failures of a specific crop. These stories matter, but it’s impossible to put discrete events into perspective without data and context.

Over the next month or two, I want to give a data-driven summary of 2024 for a few of these topics.

I won’t be covering the traditional climate-related metrics — such as temperature, sea ice, and precipitation patterns — in detail, not because they aren’t important, but because they are already covered extensively in the media (and by other climate communicators).1 It won’t be news to most of you that it’s been a hot year, with the global anomaly coming in at 1.5 to 1.6°C.

On Our World in Data we have a whole page of these climate-related metrics, which are updated frequently, if you want to dig deeper.

The first article in this three-part series will look at global food production.

Here, I’ll be relying on data from the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) World Agricultural Production reports. It produces historical estimates of food production, yields, and other indicators plus regularly updated projections for the current year.

Back in July, I looked at its outlook for global food production. As we pass the end of the year, I thought it worth seeing where we are now from its latest update in January 2025.

Note that the USDA still includes these numbers as a projection for the crop year spanning 2024 to 2025. While many crops have already had their full growing and harvest season for this marketing year, some crops in some locations are not finished. That means these are not final estimates.2

In this article, I’m focusing on the main cereal crops, plus soybean, which make up most of the world’s calories. I’ll also look at a few estimates for other key crops.

Many staple crops reached production highs

The world looks to be on track to produce more rice, wheat and soybean than ever before. Wheat just marginally; but soybean and rice by a long shot.

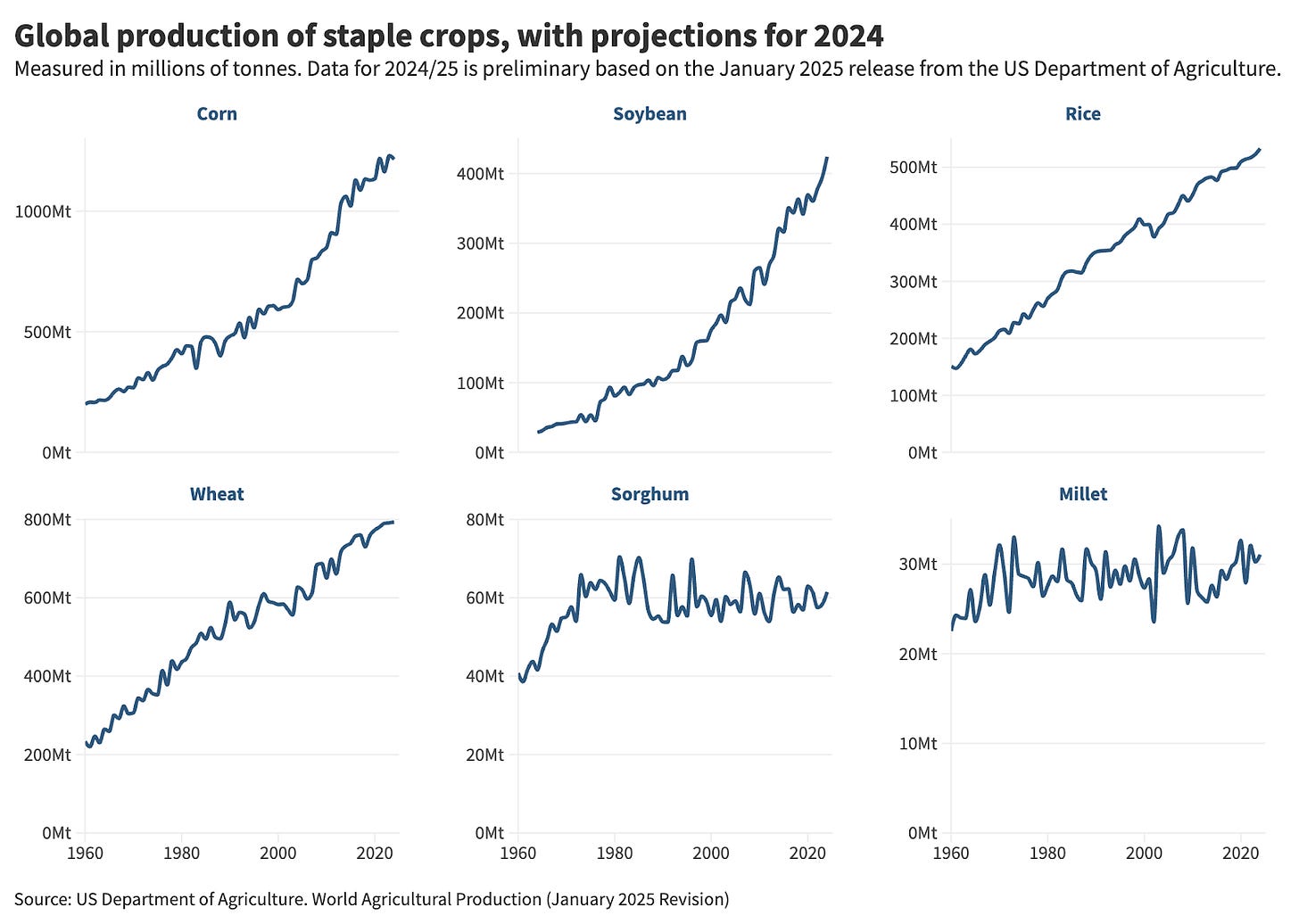

The chart below shows the historical data on global production of staple crops, with the latest projection for 2024/25.

Corn — the world’s most prolific crop — looks like it will not beat last year’s record, but will be comparable to output in 2021.

Production of sorghum and millet — a key staple across Sub-Saharan Africa — has barely grown in decades, and output this year will not be much different. As we’ll see later, yields of these crops are also very low compared to other staples. This speaks to an agricultural productivity problem in this region that I’ve written about previously, and I don’t think gets enough attention.

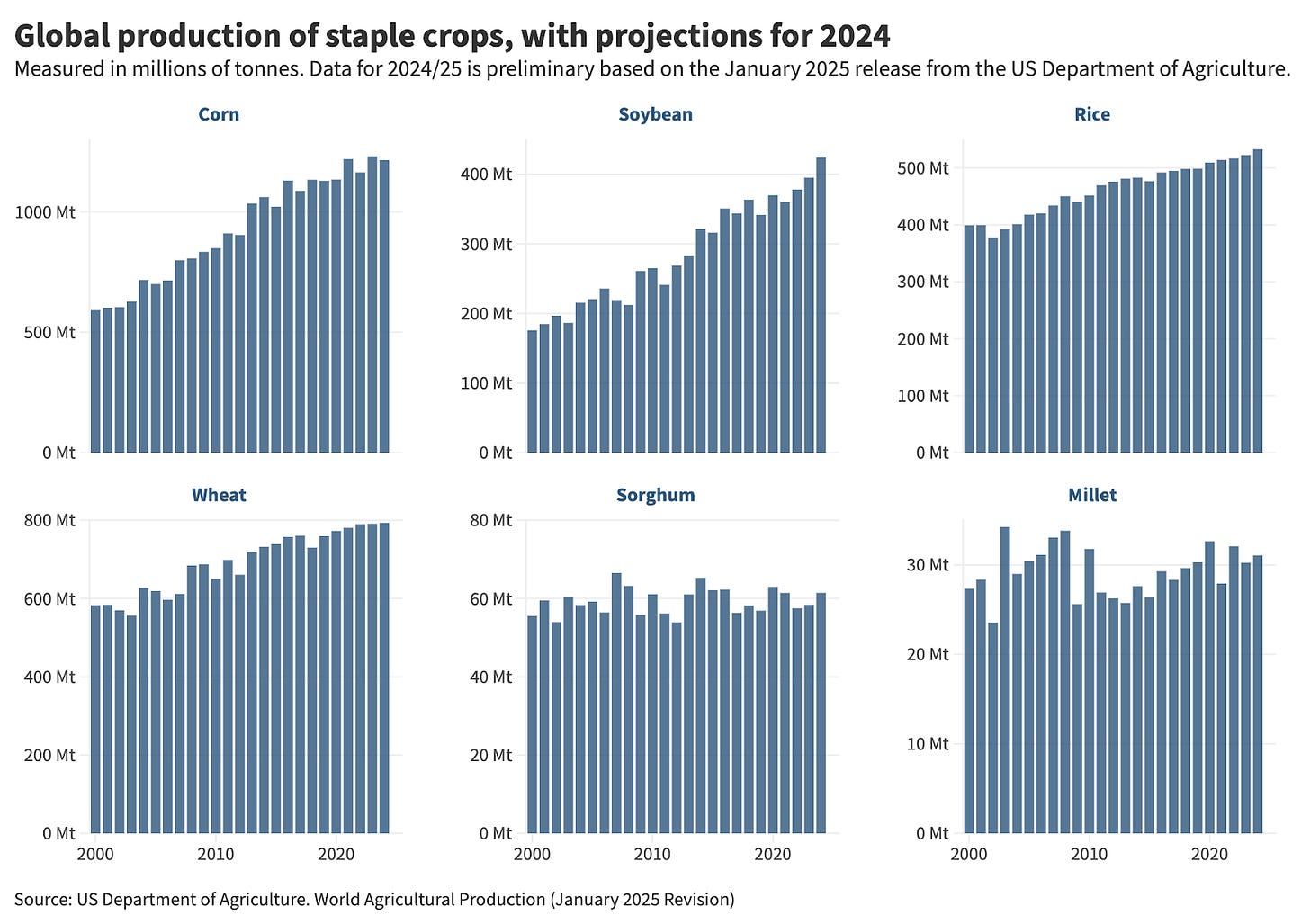

It’s hard to compare recent years’ output with the full series stretching back to 1960. So, I’ve zoomed into data from 2000 onwards in the chart below.

You can see that soybean looks on track to beat the previous year by a long way. The margins for wheat and rice are smaller. And, again, corn looks like it will be slightly down on last year’s production.

The yields of staple crops are also holding strong

You can produce more food by planting more area or improving yields. As someone who wants to see us using less land for farming, I’d rather we do the latter.

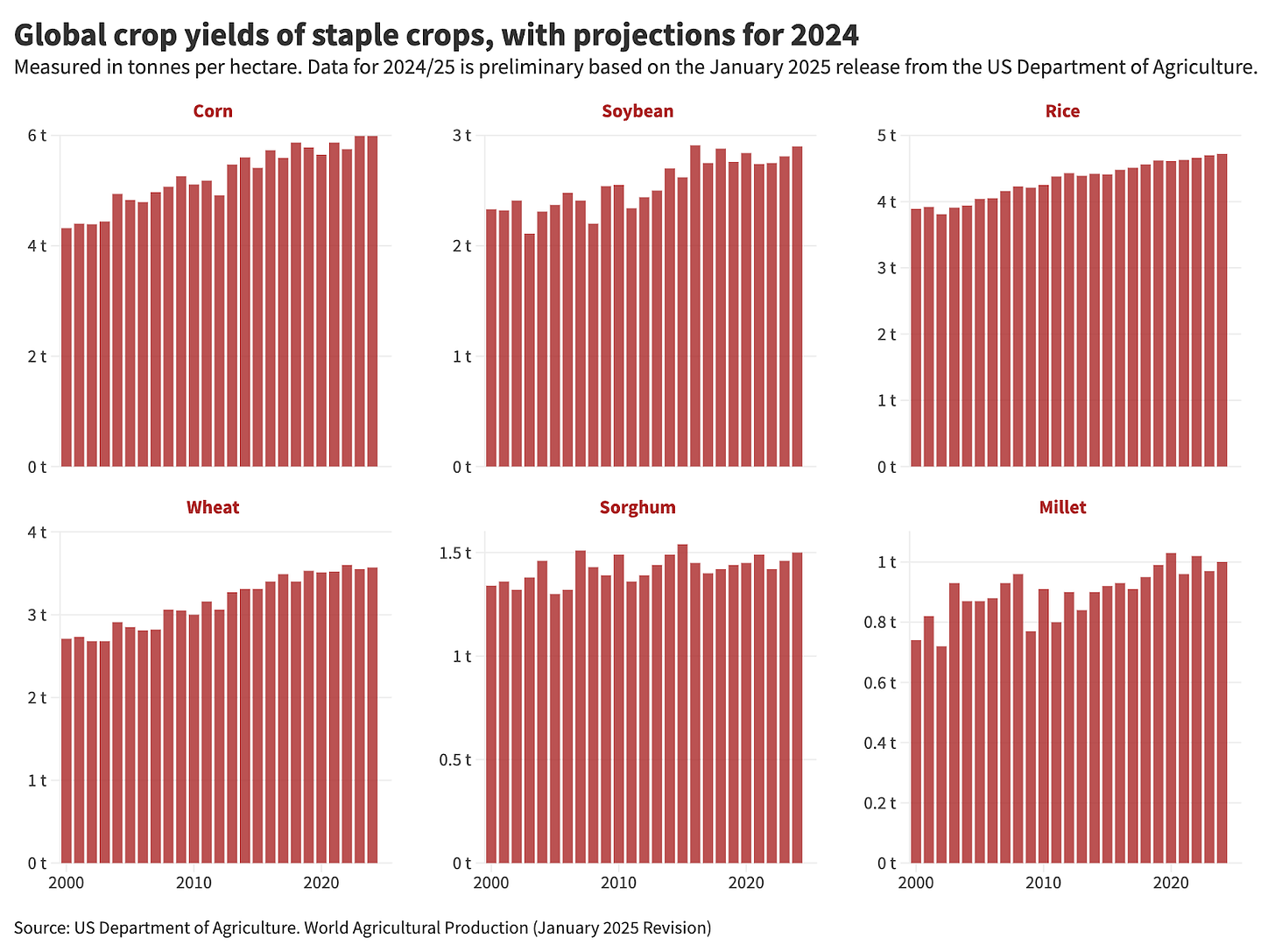

The yields of most of these staples are equal to, or slightly higher than in previous years.

Corn yields look on track to match last year’s record, which means that global production is slightly lower because less area has been planted. Rice yields also look on track to beat previous years. Soybean doesn’t look like it will produce a new record, but will be similar to the previous high in 2016. Given its big boost in production numbers this year, it must have a larger planted area than usual. Wheat yields are comparable to 2022.

AI in the Food Industry – How Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Are Transforming the Sector

AI in the Food Industry – How Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Are Transforming the Sector

Again, if you look at the y-axis scale on these charts, you can see that yields of sorghum and millet are much lower than for other crops. Corn gets up to 6 tonnes per hectare; rice is closing in on 5, wheat at 3.5 and soybean is close to 3. Sorghum and millet get less than half that at 1 to 1.5 tonnes per hectare.

Yields of other crops have been boosted over decades as a result of investments in agronomic technologies, better seed varieties, fertilisers and pesticides, irrigation, and trials on best practices. Crops without these same R&D investments have lagged behind.

A look at the production of some non-staple crops

Since I can’t give an overview of every crop, I’ve focused on the core staples that make up most of the world’s calories. But, of course, people are interested in the output of other crop groups.

Let me give a quick summary for a few:

-

Cocoa: The USDA didn’t seem to have this, but data from the International Cocoa Organization estimates that production in 2024 was down 13% on last year. Output was the lowest on record since 2014 (you can find data from 2013 onwards in the last graph here). I wrote about the cocoa price hike earlier last year.

-

Coffee: Total production is projected to be the third highest on record, beaten by output in 2018 and 2020 (but not by much: 176.5 million bags, compared to 175 million).

-

Cotton: Obviously not a food crop, but important. Joint fourth highest output on record. 2011 and 2012 were both very big years for cotton production, and maintain the top two spots. Cotton yields are expected to be the highest on record by a long way, though, at 843 kilograms per hectare compared to the previous record of 801 kilograms.

-

Sugar: Second highest production year, after 2017.

-

Fruits: Mixed trends. Some crops, such as pears, cherries, lemons, look to be on track for record production. Others, such as oranges or apples, are not (although they are close to production from previous years).

Despite record temperatures this year — and the implications for precipitation patterns that come with it — it has still been a strong year for global food production. Of course, this is not true for every crop everywhere, but at a global level, output is still strong.