The UK and European agricultural economies have been on a slow journey back to more stable conditions in the wake of the disruptive effects of Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine. While agricultural trading patterns have shifted to account for these, new shocks such as the conflict in the Middle East continue to drive economic uncertainty for the coming years.

State of global and regional economies

Global food consumption is set to expand by 1.2% per annum (p.a.) over the coming decade (2024-2033). This is slower than the preceding decade due to a slowdown in population growth, which is expected to average 0.8% p.a., bringing us to 8.7 billion people in 2033. China is expected to recede as the leader in food consumption (consumed 28% of global food over the past 10y), making space for India and SE Asia to take over (expected to make up 31% of global food consumption by 2033).

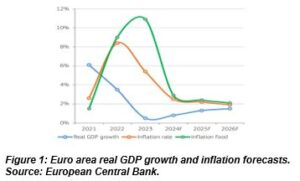

Food inflation peaked in 2023 but has since returned to a more moderate rate, averaging +2.9% for the Euro area for 2024, back in line with inflation across the economy overall (Fig. 1). However, food prices remain higher than they were before Covid, especially for sugar, olive oil, and certain vegetables.

The Bank of England lowered interest rates to 4.75% in Nov 2024, in response to the reduction in inflation across the UK economy. The new Labour government’s fiscal policy, which will increase spending, is expected to increase inflation by 0.5% at peak, taking us from current levels of around 2% to 2.5% at the end of 2025, settling to 2.2% in 2026. Interest rates are expected to be gradually rolled back to 3.5% over this timeline.

Input costs

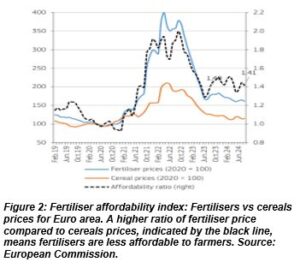

While input costs have steadily declined in recent months, the cost of fertilisers has not returned to levels similar to before the energy price shocks of 2022 (Fig. 2). Conventional fertilisers continue to be unaffordable for some farmers (phosphates are 77% more expensive than pre-crisis), leading them to explore alternatives nutrients or practices. Over the longer term, however, fertilisers are expected to become more affordable due to the reduced demand for fossil fuels across the economy, as these are increasingly replaced by renewable energy.

Pivoting for resilience

The UK and wider Euro zone have been able to maintain positive (although sometimes described as ‘sluggish’) growth following Covid, the energy crisis, and the ongoing Ukraine war. To overcome the challenges of logistical bottlenecks, workforce shortages, and labour mobility, lessons learned by local communities and food networks include a focus on local sourcing (impacting procurement channels) and an associated emphasis on healthy eating. The patterns which allowed food systems to recover from these shocks are expected to persist over the coming years. These adaptations will be necessary as new perturbations will certainly emerge:

- Conflicts in the Middle East: If the re-routing of ships to avoid the Suez Canal continues, this could have knock-on effects for energy prices. Other key maritime passages such as the Panama Canal and Black Sea are vulnerable to both geopolitics and climate change.

- Extreme weather events such as droughts, floods, and hurricanes are expected to become more frequent over the coming decade. Climate change also increases the risk of plant and animal disease outbreaks.

While local food networks can boost short-term resilience in the face of these challenges, fluid and efficient international commodity markets are equally essential to providing access to safe and nutritious food for everyone: 20% of food consumed globally is transported across an international border.

Agricultural Sector Spotlights

2022 saw historic price highs for livestock, dairy and cereals. What goes up must come down– During uncertain times, farmers and producers are encouraged to future-proof themselves as much as possible by minimising overheads, benchmarking against peers, and remaining nimble, keeping an open mind to change and innovation.

Cereals: Grain production globally was projected to see a 2.8% bump in 2024, driven by a bumper maize crop from Brazil. This depresses commodity prices for grain, despite the ongoing war in Ukraine, because trade patterns have shifted to accommodate for the conflict. Extreme and adverse weather continue to depress cereal production across the EU, both total yields and the quality of harvested grain, especially soft wheat and corn. As a result, EU exports are expected to be lower than average in the coming year and led to premiums for milling and malting quality grain.

UK farmers also experienced challenging weather for cereals this year, leading to a -6% decrease in barley output, -18% for oats, and -10% for wheat. The quality of harvested gain also takes a hit under these conditions, with less harvested wheat being suitable for bread making specification.

Oilseeds: EU oilseed production saw a decrease in the past year – Fewer fields were planted with rapeseed and sunflowers were hit with bad weather. Protein crops have been increasing by 12.6% year-on-year, largely field peas and broad beans.

Rabobank sees challenging ag environment in 2025

Rabobank sees challenging ag environment in 2025

In the UK, prices for oilseed rape (OSR) have fallen precipitously since the spike of 2022. Area planted with OSR was forecasted to decline by 19% in 2024, to the lowest area since 2021. There is strong demand for rapeseed for crushing, leading to imports from Australia and Uruguay. Forecasted prices for 2025 are middling, around £442/tonne.

Dairy: UK milk production was forecasted to contract by 1.1% in 2024 due to reduced margins, however input costs coming under control will help the situation. Predictions for domestic and international demand are somewhat pessimistic, due to slow economic growth and uncertainty around the developing situation in the Middle East.

While the herd size across the whole of the EU continues to decline, improved milk yields have allowed the supply of milk to remain stable. Plateauing input costs and raw milk prices could improve dairy farmers’ margins, on average. Dairy production is set to increase while demand remains constant, resulting in increased exports – the EU’s share of global exports of animal products could rise to 46% by 2033, driven by dairy.

Beef: UK prime cattle slaughter is pegged at 2.06 million head for 2024, a 1% rise, with beef production similar to that of 2023. However, 2025 is meant to see a 3% drop. Prices in the northern hemisphere have been enjoying historic high prices, buoyed by strong consumer demand and reduced production in the USA.

Europe and Central Asia account for 23% of global animal feed use. This market share is expected to shrink substantially over the coming decade and total feed use will shrink by 3% in Western Europe. This forecasted trend is partly due to the expected increase in extensive livestock systems for the associated environmental benefits.

Sheep: Total UK sheep meat production has decreased 8% in 2024, coming in at around 263,000 tonnes, driven by a reduced breeding flock, a reduction in rearing rate, and lamb losses due to disease and weather challenges. Carcase weights have remained similar, underlining the conclusion that this reduction is due to reduced throughputs. Farm gate prices have been strong, however, and farmers will likely achieve good prices at clean sheep slaughter in 2025 Q1.

Pigs: The UK pig market has been stable in 2024, with prices and input costs plateauing and delivering margins of around £15/head. Production has increased by around 3% compared to 2023, due mostly to higher carcase weights rather than numbers. This is set to level off in 2025, with only 0.9% increase expected. Prices for 2025 are uncertain and hinge on the dynamic and exchange rate between the UK and EU, as well as demand from China.

Climate & Environment

There is an 86% chance that at least one year over 2024-28 will be the world’s warmest ever recorded (current record set in 2023). In the coming decade, global agricultural greenhouse gas emissions are set to increase by 5%. This increase is less than the increase in total agricultural output, indicating a decrease in carbon intensity of agricultural production, enabled by improvements to productivity rather than expanded land use or herd size. The World Bank stipulates transitioning the global food system could eliminate one third of global emissions by 2050 but will cost $260 billion per year.

The UK and EU’s emphasis on sustainability in food production is world leading. However, more stringent requirements may increase the cost of production, which threatens the competitiveness of exports in a global market. Farmers should prioritise sustainability innovations which have productivity benefits, as this will help mitigate additional costs, as well as increase resilience to external shocks. Governments need to provide clear strategies and adequate resource to support rural livelihoods and food security.