Since 2014, four abattoirs have been set up in Kenya to meet demand. The meat is considered a delicacy in China and the skins are processed to create ejiao, a traditional remedy used to treat everything from anaemia to dizziness. However, according to a recent report by the African Network for Animal Welfare (ANAW), the slaughterhouses are operating at below half their capacity.

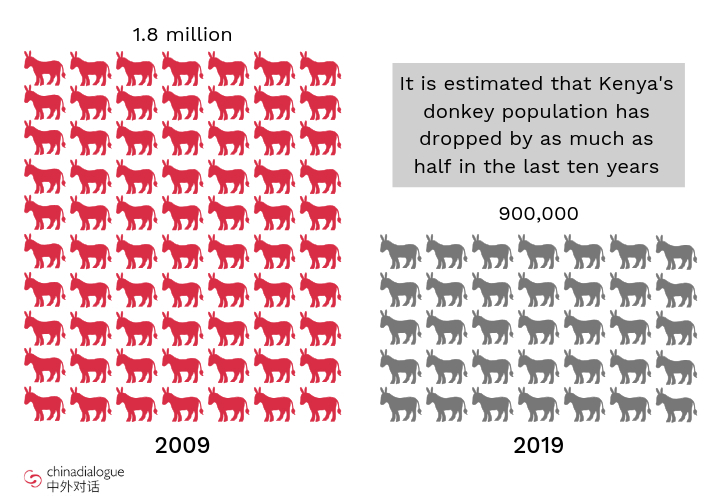

The report, which was written earlier this year but is so far unreleased, estimates that donkey numbers in Kenya have fallen by as much as half over the past ten years, from 1.8 million animals in 2009 to about 900,000 today.

ANAW chief operations director Kahindi Lekalhaile warns that abattoirs are making the trade unsustainable by slaughtering too many animals. Donkeys are slow to reproduce, with a gestation period of 11-14 months.

A booming market

High demand and declining numbers have increased the value of donkeys. According to Joseph Ng’ethe, a water vendor who relies on his donkey to make a living, an animal can be sold for 15,000 to 25,000 Kenyan shillings (US$145-242), up from 6,000-8,000 shillings (US$58-78) four years ago. Male donkeys tend to fetch a higher price as do animals from areas near highways and towns.

There is now a shortage of breeding males and an increase in thefts. Ng’ethe notes that in his area, 60 kilometres southwest of the capital Nairobi, there’s a new case of donkey theft each week. “During the day, we used to leave our donkeys alone in the fields to roam and graze freely, but not anymore. The risk of them being stolen is too high.” Ng’ethe wouldn’t be able to afford to replace his animal.

In remote regions, donkeys play an even more vital role in everyday life. According to conservationist Noor Ali, “donkeys are everything” in the

Ejiao driving demand

The popularity of ejiao in China has grown with the country’s prosperity. Marketing of healthy lifestyles has helped Dong-E-E-Jiao, the country’s largest producer, to increase the cost of ejiao products 20 times since 2005. Meanwhile, China’s donkey population has fallen rapidly, from 9.4 million in 1996 to 2.5 million in 2018.

This is forcing ejiao producers to source donkeys from elsewhere. “As donkeys are no longer an important part of China’s agriculture sector, the domestic supply of donkeys could not meet the demand of the ejia industry anymore,” Qin Yufeng, chief executive officer of Dong-E-E-Jiao, said in 2017.

Kenya’s newest donkey abattoir is located in Machakos county to the southeast of Nairobi. It was set up late last year by Chinese multinational the Fuhai Group. Manager Patrick Kithyoko says the operation slaughters 300 to 400 animals a day, well below its maximum capacity of 1,000.

Kithyoko says the abattoir pays well for the animals it slaughters but with fewer available, it has yet to stockpile enough skins and meat to make exporting to China cost effective. “We hope to attain the right tonnage to be able to ship out products by December,” he said.

The Fuhai abattoir joins three others in Kenya, all competing for a limited number of animals. With donkeys in such high demand, a thriving cross-border trade has developed. Kithyoko sources animals from across East Africa. Noor Ali corroborates, reporting that donkeys are a new addition to livestock on sale at the busy Sololo market on the border with Ethiopia.

Welfare standards

With donkeys now travelling significant distances to reach the abattoirs, their welfare is a growing concern. According to a recent report by the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA)-Asia, the animals are squeezed into trucks without food and water for journeys that can take up to two days. Many of them die en route, and the poor conditions continue in the holding pens before slaughter.

“There are virtually no laws against the abuse of animals in farms or slaughterhouses in Kenya, so none of the violence captured in our video footage is punishable from a legal standpoint,” says Nirali Shah, PETA-Asia’s special projects coordinator.

These findings are echoed in the ANAW report, which accuses all four of Kenya’s abattoirs of failure to comply with international animal welfare standards, including those set by the World Trade Organisation and the World Organisation for Animal Health.

According to Nina Odongo, acting head of the Kenya Society for the Protection and Care of Animals, some of the cruel practices include the slaughter of pregnant donkeys.

Calls to ban the trade

Odongo says the Kenyan authorities should not have licenced the abattoirs without first setting up a breeding programme to meet demand and conducting a feasibility study into the industry’s sustainability.

ANAW’s Kahindi Lekalhaile agrees. “Studies have shown that communities benefit more when they keep their animals,” he says. “We are therefore advocating for policy reform to curtail this trade.”

PETA is also pressuring the government. Shah points out that 12 other African countries have closed Chinese-funded abattoirs and developed policies to control the export of donkey skins to China. She says PETA has written to the Ministry of Agriculture demanding they follow suit with “immediate action to ban all Kenyan donkey slaughterhouses”.

“The reality is that there are more effective alternatives to ejiao, such as modern drugs and herbal medicines, that don’t require animals to be killed,” she says. “Most people have no idea that donkeys are suffering so terribly or what this cruel industry is all about.”

However, Nicholas Ayore, deputy director of the Directorate of Veterinary Services says that licensed abattoirs are closely monitored to ensure they adhere to acceptable standards for handling and slaughter. He denies that donkey numbers are declining as a result of the trade.

“A ban on the trade would not be something as simple as the activists are assuming. It would have to be guided by a policy paper after research showing that donkey populations [were] on the decline,” he says.

NOTICE- This is a video of 2016- Prices and information may differ-